If you’re planning to do more than one set of an exercise, start by performing eight to ten repetitions with a light weight. A warm-up set is like a dress rehearsal for the real thing — a way of reminding your muscles to hit their marks when you go live. Even monstrous bodybuilders do warm-up sets. Sometimes you’ll see a human hunk of muscle bench-pressing with just the 45-pound bar. Just as you’re thinking, “What a wimp,” he piles on so many weight plates that the bar starts groaning. Then you realize that the first set was just his warm-up.

If you’re planning to do more than one set of an exercise, start by performing eight to ten repetitions with a light weight. A warm-up set is like a dress rehearsal for the real thing — a way of reminding your muscles to hit their marks when you go live. Even monstrous bodybuilders do warm-up sets. Sometimes you’ll see a human hunk of muscle bench-pressing with just the 45-pound bar. Just as you’re thinking, “What a wimp,” he piles on so many weight plates that the bar starts groaning. Then you realize that the first set was just his warm-up.If you get too cocky and head straight for the heavy weights, you risk injuring yourself. With weights that are too heavy for you, you’re playing with some risky behaviors.

- Losing control of the weight

- Dropping the weight on yourself or on someone else

- Straining so hard to lift the weight that you tear a muscle

- Ending up so sore that you can barely lift your feet up high enough to climb stairs.

One or a combination of these accidents can cause a lapse in your workout as you may have to take time off to recover. Be smart and start with lighter weights — weights that you can lift for more reps before you reach fatigue. Then challenge your body by increasing the weight over time. A personal trainer at the gym can also help you target a starting weight for your repetitions.

Lifting weights too quickly doesn’t challenge muscles effectively and is a pretty reliable way to injure yourself. When you’re pressing, pushing, lifting, or extending at the speed of a greyhound, you can’t stop mid-rep if weight plates come loose, you’re positioned incorrectly, or something just doesn’t feel right. So take at least two seconds to lift a weight and two to four seconds to lower it. Some experts feel that you should move even slower than that. If you’re banging and clanging, slow down your pace.

Lifting weights too quickly doesn’t challenge muscles effectively and is a pretty reliable way to injure yourself. When you’re pressing, pushing, lifting, or extending at the speed of a greyhound, you can’t stop mid-rep if weight plates come loose, you’re positioned incorrectly, or something just doesn’t feel right. So take at least two seconds to lift a weight and two to four seconds to lower it. Some experts feel that you should move even slower than that. If you’re banging and clanging, slow down your pace.

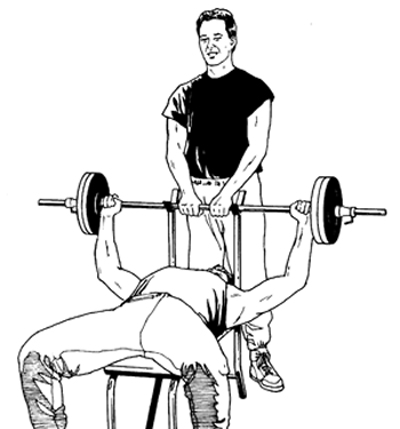

A weight bench is what you may expect: a sturdy, padded bench that you lie, sit, or kneel on to lift weights. To get the most out of free weights, benches are a must.

A weight bench is what you may expect: a sturdy, padded bench that you lie, sit, or kneel on to lift weights. To get the most out of free weights, benches are a must.